Let’s play a little thought experiment.

You’re starting a new business. All great.

What’s the first thing you start to think about?

Your technical infrastructure?

The design of your product?

Marketing?

How about your business model?

Oh yeah, that thing.

A business model is all about finding a way to attract customers who pay you more money than it costs you to find and convert them.

After your product/market fit, your business model is the most important consideration if you’re to save your business from the startup graveyard.

This sounds complicated — how do you figure out and track whether each customer is profitable when you’re dealing with hundreds (even thousands) of leads and prospects on a daily basis?

This is where the value of subscription metrics comes to the fore — and specifically the customer acquisition cost (CAC) and the customer lifetime value (LTV).

What is the Customer Acquisition Cost?

CAC stands for customer acquisition cost. It is a measure of the total cost your business incurs to turn someone who’s never heard of your company into a paying customer.

To calculate CAC take all the marketing spend in a given period and divide it by the number of customers attracted in that same period:

CAC = Total sales & marketing spend (salaries, tools, ad budgets/etc.) / Number of customers won

CAC can be calculated as a number that reflects the average customer your business attracts. Or it can be segmented by marketing channel, geography/market, cohort, or any other way that makes sense to your business.

How to calculate CAC

On the ground level, the formula for CAC looks simple, but dig a little deeper into the details and the discussion gets heated.

Every team has their own slightly different way of calculating the cost of customer acquisition. The discussion usually rotates around questions like:

- Should I count money spent on marketing tools into it?

- Should I include salaries in the calculation?

- What if I have an employee who splits their time between writing content and supporting customers? How do I account for them in the CAC calculation?

- What about your office lease and similar expenses, should they also be included?

These questions are all important and worth spending some time on. Generally, if any part of your team is working on an activity that’s touching on acquiring customers all their expenses should be included in the calculation — salaries, rent, and so on.

My advice is that once you have picked a way to calculate CAC, you should try to stick with it — the metric is more useful when the formula stays the same, so you can compare it over time.

I also want to suggest a slightly nuanced way to calculate and think about CAC. For that, I’d like to use Lincoln Murphy’s distinction between Simple and Fully-Loaded CAC.

Note: We don’t calculate CAC in ChartMogul because of the subjectivity of how different businesses calculate it and use it. However, our users use attributes to enrich their data and use segmentation to understand their metrics (including CAC) better.

Some customers use the LTV charts in ChartMogul to compare with numbers that they are generating from marketing spend and sales time. Here are a couple of pieces on how to use LTV and CAC in an actionable way:

Simple vs. Fully-Loaded CAC

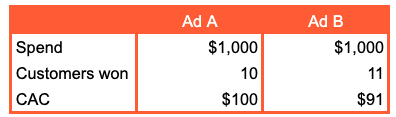

Let’s say you’re trying to compare two ads and decide which one to allocate more budget to.

(We’ll ignore the different customers/LTV each might produce for now.)

Assuming you’d spent approximately the same amount of time coming up with each ad, is it really worth adding in all the costs related to employee time and tools to get the perfect CAC number?

Yeah, I don’t think so either.

Simple CAC is the perfect tool when you need to make a quick tactical decision.

Fully-Loaded CAC that includes a robust calculation of all inputs that go into acquiring a customer is a much better option for strategic decisions perhaps when deciding on how to optimize and prioritize marketing channels.

How often should I be looking at CAC?

As often as it helps you make a decision about your business.

In many cases, this would mean daily — simple and fully-loaded CACs are useful here because they can help you understand various aspects of your business and make better decisions.

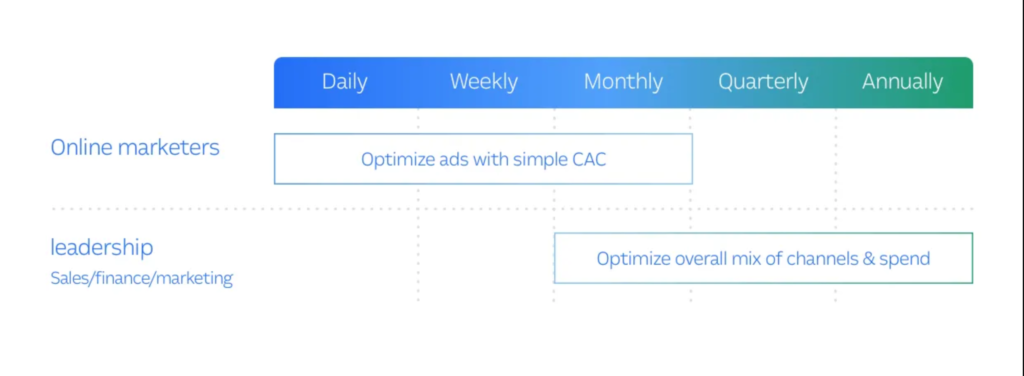

Intercom’s model presents a useful way to think about this:

We all use simple CAC calculations to make daily decisions about how to spend our time and marketing budget.

Once a quarter, or even maybe once every 6-12 months, you can use the extended fully-loaded CAC model to measure the success of your overall marketing strategy and make changes if necessary.

Why CAC is so important for SaaS businesses

The cost of customer acquisition is one of the most important metrics — SaaS businesses must keep a close eye on it at all times because of their unique circumstances.

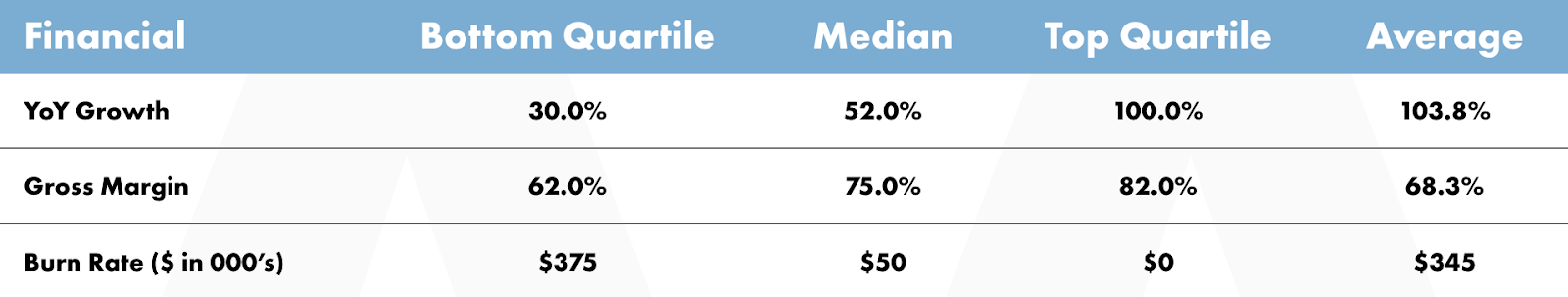

Generally, SaaS companies have a low cost of goods sold (or COGS), typically 20-30% on average.

Source: OpenView Expansion SaaS Benchmarks Report

That allows these companies to subscribe customers on a very low entry fee where they look to earn a profit over time as a customer is using the software and paying subscription fees over many months (also known as the lifetime value or LTV of a customer).

Typically developing the software is much more expensive than the initial (subscription) fee a customer would pay. This is recouped over time as you attract more paying customers and as they remain subscribers for longer.

The customer acquisition cost works much the same way because of the focus on retaining a customer as long as possible — that means you can spend more on acquiring a customer than they’re going to pay you initially.

You’ll often see a popular ratio mentioned when it comes to the relationship between CAC and LTV:

LTV = 3xCAC

If your average LTV is $600, that means you can spend $200 per paying customer.

Where does the 3:1 ratio come from?

The low COGS ratio in SaaS companies can be misleading. These companies have low direct costs, but they spend a lot on developing and bringing that product to their customers.

Generally, most SaaS companies have 3 large expenses on their profit and loss statements:

- Research & Development (or the cost of creating the product);

- Sales & Marketing (or the cost of bringing that product to the people who аre best suited to use it, i.e. CAC);

- General & Administrative (or the cost of organizing the work in the previous two).

If you look at the majority of software companies today, you’ll notice that their expenses are roughly equally divided between the 3 areas outlined above.

It is so common, that you’ll see companies called out if they dare ‘break’ the parity.

If these 3 are roughly equal, that means a customer needs to pay roughly 3 times CAC to repay the investment made across the organization in bringing the specific product to them.

During Year 1: you repay your S&M expenses (CAC).

Thibaud Clement, Loomly

During Year 2: you repay your R&D expenses.

During Year 3: you repay your G&Q expenses.

During Year 4: you start turning a profit.

This is where the 3xCAC = LTV formula comes from.

As mentioned, not all companies have the same cost structure, therefore not all of them need to follow the 3:1 ratio. Check out this post for a detailed discussion on how this changes and why it might still work.

CAC is a proxy for the distribution

Peter Thiel is famously quoted for saying that startups fail because of bad distribution more than they do because of a bad product.

Most businesses actually get zero distribution channels to work. Poor distribution — not product — is the number one cause of failure.

Peter Thiel

Let’s dig a little deeper into that.

There are many ways in which you can bring a SaaS product in front of customers:

- You can produce content and pay site owners, Facebook, and Twitter to bring it in front of your audience.

- You can buy ads from Google, so they place your site on the front row of their search results.

- You can incentivize influencers in your niche to promote your product.

You can always spend more money to acquire customers — you can bid on the crazy-expensive keywords on Google or run a partnership with your favorite NBA star.

But no matter what tactic and channels you choose and how much you spend in each of them, your business won’t make it unless you find a place where customers are paying more to use your product than you pay to reach and convince them.

That’s the question of distribution Thiel captures so masterfully in a sentence.

Use CAC to align your business model

All metrics are great simplifiers. You can use them to think through a complex problem and measure your progress towards a goal you set for it.

LTV simplifies your thinking about positioning (i.e. what customers you’re attracting) and retention (how long you’re keeping them).

ARPU helps you understand how you’re progressing towards capturing more sophisticated customers.

CAC (especially when compared to LTV) is a distillation of your business model.

Understanding it will help you nail down your marketing strategy — from positioning to the channels you use to your hiring plan.