Enough has been written about the subscription economy.

In the last five years, the subscription economy has been growing 200% a year. We all heard about Dollar Shave Club’s recent billion-dollar buyout. And the internet, from tech and business journalism to company blogs, is rife with analysis of how subscription services are changing not only business models but entire industries.

There’s now a subscription to serve nearly every need of nearly any lifestyle. It’s not just Stitchfix and Netflix anymore, not just razors and makeup. It’s weekly groceries and meal plans, laundry, yoga, tickets to see your favorite bands, online education, medical care and mental health counseling — plus thousands of niche interests in between. Check out My Subscription Addiction.

But no one is talking about the subscribers.

What about today’s consumers is making this mass disruption possible? How and why is this age of consumers so hooked on subscription services? I investigated this question, as a professional in the subscription economy (SaaS, specifically) as well as a millennial who is (at least somewhat) in touch with the trends of her generation. Tired stereotypes of millennials nudged me along at first.

It’s a good Tweet, I admit. But rather than assume this generation — the 92 million people born from 1980-2000, the largest generation in American history — is full of lazy folks, I evaluated characteristics of millennials against popular culture and consumer behavior.

I found that the subscriber and the subscription economy reflect each other, like an infinity mirror of our zeitgeist. In that reflection, the common values between the two are quite clear; they’re the consumer values that define our time. So tied, the subscriber and the subscription economy shape and mold one another with each recurring payment, the subscriber slipping more and more into that embrace. And as a result of this cradling, this coddling, today’s subscriber is not exactly the “empowered consumer” the business world assumes she is.

But let’s start with memes.

Indulgence.

The first trait is summed up in two words: “treat yo’self.”

This phrase first popped into our collective consciousness in 2011, when a Parks and Recreation episode featured a bit about two characters who spend the whole day doing reasonably luxurious activities, celebrating themselves. The sketch was so successful, the meme so consistently viral, that the show reprised it for episodes years later, in 2015. And it may well have defined a generation. I hear it regularly to this day; when I mention that I may take an afternoon nap, a friend responds, “Treat yourself!”

The “treat yo’self” ethos is strong in the subscription economy. FastCompany quotes Marshal Cohen, of consumer market research group NPD, as saying:

“Millennial consumers, in particular, love the idea of self-indulgence, and subscription companies really understand this.” – Marshal Cohen

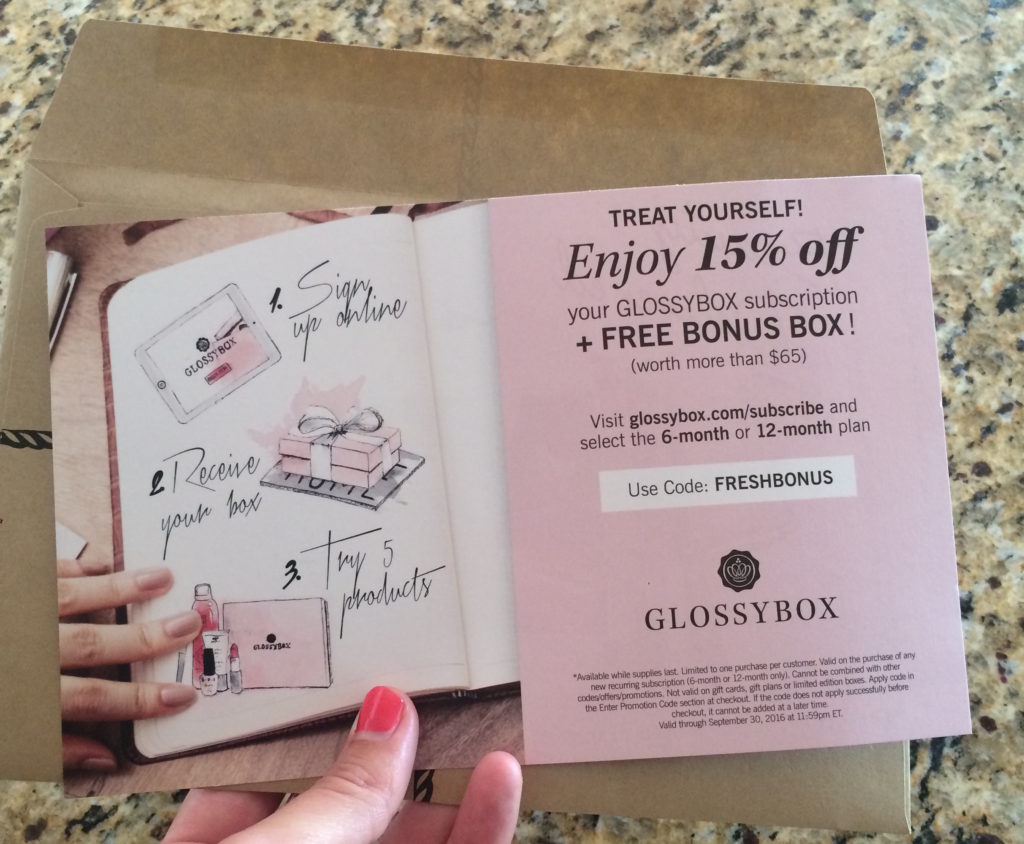

The context was specifically about subscription boxes, delivered like a monthly birthday present. Indeed, as I was writing this story, a friend familiar with my research points sent me a photo of some promotional material she got in the mail. It was for a cosmetics subscription box called GLOSSYBOX. Lo and behold, it says “Treat yourself!” right at the top.

But Cohen’s point about self-indulgence applies beyond monthly box deliveries to other subscription services, such as Netflix. Self-indulgence takes the form of bingeing an entire season of a TV show. As soon as Netflix noticed this user behavior, they started releasing full seasons of their original shows all at once. They catered to the indulgence of their audience, or, like any good company, to the behavior of their customer.

An extension of the self-indulgence is the customization that comes along with continued membership. As they get customer feedback, most every subscription service curates and tailors future offerings to the tastes and preferences of the subscriber, which makes for a cozier and cozier fit.

Convenience.

Hardly exclusive to any generation or any consumer, convenience is king in American culture. That’s why so many people have their own cars and so many eateries (and banks and pharmacies) have drive-thrus. It has a huge influence on consumer behavior, evident in millennial spending habits. TD Bank found that while Millennials actually spend less than generations before them, the only category where they spend more is on fast food and coffee. A point which Inc. columnist Bill Murphy interpreted as:

“If you want to create a product or service that Millennial consumers are likely to want, all else being equal, it seems you can’t go wrong with efficiency and convenience. They want quality, sure — but they also don’t have time to sit around and wait.” – Bill Murphy

Predictable monthly delivery of something relatively mundane, like toiletries or groceries; constant access to music or movies; recurring, no-brainer payments — these are all parts of the convenience.

Of course this element is closely tied to the other economy that’s blossomed with the coming of age of Millennials: the on-demand economy. It only takes an app and a tap of a button to fill a need. Instant gratification and no-friction purchases dovetail into a supremely convenient consumer experience. And indeed, on-demand and subscription models are starting to merge; no doubt the on-demand companies don’t want to miss out on the benefits of recurring revenue. PostMates, a service that delivers anything you need from virtually any brick-and-mortar store in your area, just announced a new subscription plan. So did Luxe, an on-demand valet parking service.

Access, Not Ownership.

Chances are you’ve heard of KonMari, the eponymously-branded lifestyle method that underpins the global bestseller, The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing.

This book, which teaches readers how to simplify their lives by purging and organizing their possessions, took the world by storm. It’s been a bestseller in most major economies: the US, Japan, Germany, and the UK. Marie Kondo, the author, has done the daytime talk show circuit and been featured in an array of publications, from Cosmopolitan to the Wall Street Journal. Marie Kondo tapped into something.

“Consumer behavior, especially among younger people, is changing, and the need to own and house goods—from music to cars to physical documents—is waning.” – Fortune

Indeed, statistics and surveys show that we’re getting tired of purchasing and accumulating things. Havas Worldwide, a market research organization, found that around half of consumers in eight key markets “had thrown out or thought about throwing out lots of stuff to declutter my life and my home.”

Add to this the recent popularity of reality TV shows about hoarders, particularly A&E’s “Hoarders” (100+ episodes) and TLC’s “Hoarding: Buried Alive” (75+). These shows undoubtedly exploit their subjects and the underlying psychological condition, as reality television typically does, but what accounts for the long-standing popularity of this particular phenomenon? In a climate of purging, hoarding becomes a fetish.

Tien Tzou, CEO of early SaaS company Zuora and coiner of the very term “subscription economy,” defines the subscription economy as “the idea of throwing ownership to the curb.” We don’t need to own the album or the movie, we can just go to Spotify or Netflix.

Instead of ownership, we want access. 80% of today’s consumers demand new consumption models, be that subscribing, sharing, or leasing. This is where another coined economy overlaps with subscriptions: the sharing economy. And again, sharing services are dipping their toe in subscription waters. Uber experimented, very quietly, with a subscription model called Uber Pool Pass, available to a limited number of Boston customers for the month of June.

The Empowered Consumer.

All of these traits depict an economy that bends over backward to serve the whims of its customers, and to some extent, that’s true. The subscription business model relies and thrives on keeping their customers happy. The live-and-die metrics are retention and churn. Customer Success is a new department created primarily to keep subscription customers on board. Even the attitude of Sales is changing. Mattermark recently quoted Shopify’s chief sales scientist, Loren Padelford, on the shift:

“Our job is to do what our customers want. Customers are in control of the sales process now.” – Loren Padelford

The subscription itself is a commitment on the subscriber’s terms, tailored to their tastes, easily canceled, easily transferred to one of the other competing services that are just a screen tap away. Subscribers know they can wield loyalty as a tool to get what they want from these companies. And so it feels the ball is completely in the consumer’s court.

But is the subscription model actually empowering?

All of the argued positives could be flipped as negatives. Because in different subtle ways, the consumer is giving up control, agency, and independence.

Automatic payments make it so that the consumer is stuck into recurring billing unless taking deliberate steps to stop the vendor from taking their money. Whereas in more traditional models, the consumer takes deliberate action to give the vendor their money.

That’s not the only thing subscribers put on auto-pilot. After choosing to subscribe to the service, the subscriber forfeits choice in favor of curation. And curation’s gradual process of customization, that cozy fit I mentioned before, has a downside, too.

A curated list — of movies on demand, of products in a box, of recipes to cook that week — is really just a consciously curtailed selection. While this curation is often billed as product “discovery” for the consumer, the discovery takes place within an inherently limited pool. And that pool shrinks as the subscription goes on. Over time the subscriber’s marketing profile — their preferences and spending habits — matures and gets so precise that the vendor learns exactly what to provide to ensure consumer happiness.

Where’s the discovery in such an echo chamber? This critique is common when it comes to curated news, such as Apple News or social media feeds. You are shown stories that “are likely to interest you,” as well as the views and opinions of people who are probably very like-minded. So it begs the question whether this “news” is accomplishing its task of actually informing you.

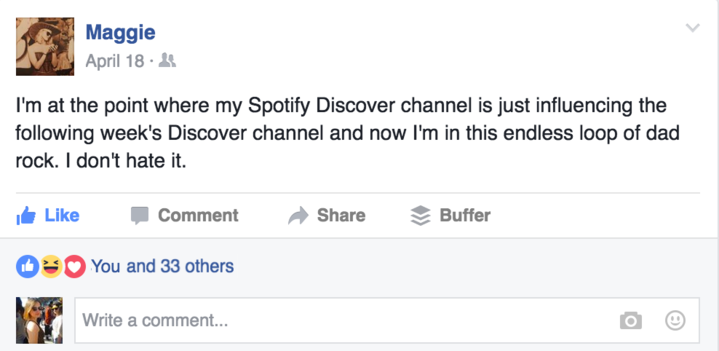

In the SaaS context, a great example is Spotify’s aptly named “Discover Weekly” playlist, a weekly mix of songs that Spotify’s algorithm suggests for you, keyed off the other tracks you’ve recently played. Based on what it perceives to be your taste in music, the list is meant to expose you to other artists you might like. But if you’re only listening to “Discover Weekly,” then the next week’s list will populate off of the last week’s, and on and on in a solipsistic cycle until variety and discovery are eliminated entirely. This exact thing happened to my friend.

And that’s just it: she didn’t hate it. Which brings me back to my question about why this age of consumers is so hooked on subscriptions.

I’d argue that it’s the very limiting and disempowering effects of the subscription model that seduce consumers — and keep them happy.

Subscriptions, take the wheel.

Maybe consumers value the freedom of choice, but a joy of the subscription model is that you don’t do the choosing. It’s a luxury to receive hand-picked products and services — which arrive on our doorstep or on our screen — which we experience as gifts and favors — and to not put in the effort of the search. We don’t care about sacrificing control or discovery as long as someone else is making the decisions for once. Which leads to a characterization of our time that hasn’t come up yet. The Information Age. In a time of information overload, we suffer from decision fatigue, or what others might call “analysis paralysis.”

“The more choices you make throughout the day, the harder each one becomes for your brain, and eventually it looks for shortcuts.” – The New York Times

Perhaps the never-ending, limitless world of products is actually confining, debilitating. I once met the Irish poet Theo Dorgan, who mused that today we live in a “prison of infinite choice.” Dorgan’s observation reflects a common response to decision fatigue, which is to do nothing: “Instead of agonizing over decisions, avoid any choice.” We are stuck. And subscription services are consumer shortcuts.

So, in that way, perhaps the subscription model is actually liberating. Subscriptions remove the burden of too much information. They relieve us of the need to constantly stay up-to-date, to research, to review, to compare. They free us from that prison of indecision and the responsibility of being a hyper-conscious consumer. A liberation, though mindless, that’s seductive indeed.