In all of the metrics-oriented discussions I’ve had with SaaS founders in recent years, customer lifetime value (LTV) has been by far the most polarizing of all metrics.

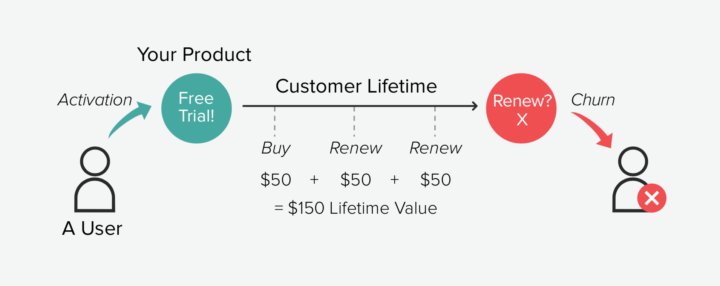

The promise of LTV is so compelling: a true understanding of the complete contribution a customer’s value across their entire lifetime in your product, taking into account revenue expansion and changes to MRR.

There’s really no argument about the value and utility of LTV — that’s completely clear. With it, businesses are able to confidently assign budget to customer acquisition (CAC) with the knowledge that the investment will more than pay off. The general agreement in SaaS is that a CAC:LTV ratio of 1:3 is a good target, i.e. the cost to acquire a customer will be paid back three times over.

Predicting the future is hard

“We are using a formula to predict the future, and the future, by it’s very definition is not predictable…The value in this analysis is to get enough accuracy to make useful business decisions, such as what factors to look at to improve profitability…”

David Skok

So what’s the problem with LTV as a metric? Looking at the data of a number of SaaS startups, it’s clear that it’s difficult to get to an LTV estimate that’s anywhere near consistent or accurate.

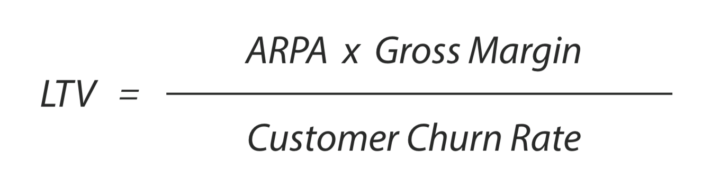

Particularly in businesses with a lower customer count, the cancellation of a single customer has an over-sized impact on churn rate. This directly impacts LTV, where the usual formula is a product of churn rate and average revenue per account (ARPA). These businesses can see LTV fluctuating wildly from one month to the next, meaning that attempts to gauge or plan acquisition spend are often futile.

The basic LTV formula

The bottom line is this: LTV is a forward-looking prediction rather than a measurement, based on a very basic model of customer churn. So is there anything better out there that we can use in these cases?

I’d propose two variations on “traditional” LTV:

- LTV across a fixed period

- “Actual” LTV

LTV across a fixed period

Investors sometimes like to sample the LTV of a startup across a fixed period, which is usually 12 months. This modified formula answers the question “how much value to customers deliver in a 12-month period?” Rather than trying to estimate the complete customer lifetime.

Metrics like twelve-month LTV work well in businesses with low churn (where there’s very little “full lifetime” data to go on). The result is a more stable LTV which can drive higher confidence in acquisition spend.

This variation also does a good job of capturing any revenue expansion customers might see over the period.

“Actual” LTV

If one of the main issues with LTV is in the prediction, what if we eliminate that and just look at the average real LTV of customers who’ve already churned? If you have some data to go on (i.e. you’ve had a number of customers both subscribe and churn over time), this can give a more realistic picture of LTV.

The only problem with this variation is that it can give an overly pessimistic view of customer value because it only looks at customers who have churned. Those perpetually happy customers who have stuck around and are still subscribed are not included here. In this case it maybe more useful to track and focus on increasing the delta rather than read into absolute numbers too much.

Getting experimental

There’s a lot more you could do to tweak your measurement of LTV and get to a metric that’s highly tailored to your product.

So which metric should you choose? It depends on:

- Who’s asking

- What questions you’re trying to answer about your business

Segmentation is a great way to bring far more actionable results, allowing you to answer questions like:

“What’s the LTV of customers on the Pro plan?”

“What’s the 12-month LTV of customers who had a high-touch onboarding process vs. self-service onboarding?”

You can use a tool like ChartMogul to answer those questions.

Just remember that when you see the common LTV metric, it is always a forward-looking estimation rather than a precise measurement. Without getting into increasingly complex modeling, it’s never easy to give a completely accurate picture of your business. That doesn’t mean it can’t be useful though!

Further reading

If you really want to get advanced with predicting the future, David Skok presents an advanced version of the classic LTV formula that applies a “discount factor” to get to a more realistic estimate.

You can also find a summarized version of this (and more LTV tips) in our SaaS LTV Cheat Sheet which you can download for free!